Ideation Drawing -The Route to Better Composition

Do you want to maximise the potential of your ideas? Ideation drawing is the solution. It involves quickly sketching out initial concepts for a project, without worrying about perfection. The focus is on generating a variety of first concept ideas and exploring different compositional possibilities. I’ve learned that this method can lead to more fully realised and successful artwork. By producing a large number of rough sketches, you increase the chances of discovering the best solution. By sketching out multiple variations of an idea, you’re able to refine and improve upon it. This time it’s about quantity over quality. Let’s look at how you can try it out and see the improvements for yourself.

- What is the purpose of ideation drawing?

- What does ideation drawing look like?

- The characteristics of good ideation drawing

- Why is ideation drawing so difficult?

- How to improve at ideation drawing

- What to focus on when you are doing ideation drawing

- How I learned the value of ideation

- Does every project need ideation drawing?

- Further Reading

What is the purpose of ideation drawing?

Have you wondered how do other artists come up with ideas for their of work? There are a number of stages to this process. Like many of the students I see in classes today; when I was an art student and had an idea for a piece of work, the first thought that I had about it was usually more or less its final form. We weren’t taught to do ideation drawing or colour studies.

It didn’t occur to me naturally to do this as it appeared to be too time consuming. You just want to get on with it and make the piece of work right? Two learning experiences changed my mind about this and I’ll tell you about them later.

What is missing from the process if you work like that?

If you skip the ideation stage you are missing out on a more thorough exploration of what the idea actually is and what it’s best form might be. You are potentially underselling your idea and not exploring the potential for the best outcome from that idea. Ideation drawing technique helps avoid this.

Ideation drawing is a method of sketching out your first ideas for a piece of work roughly and to an unfinished and unpolished standard. You are focussing on presenting the idea in the drawing rather than making something that is beautiful to look at.

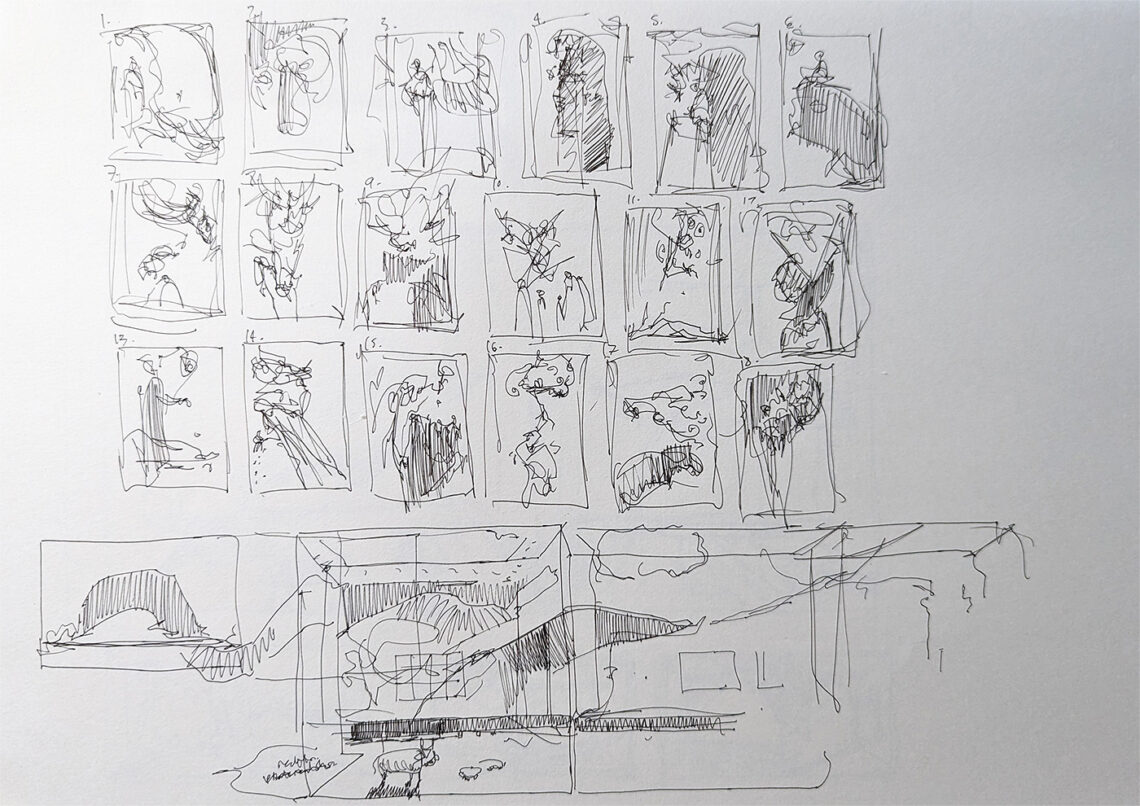

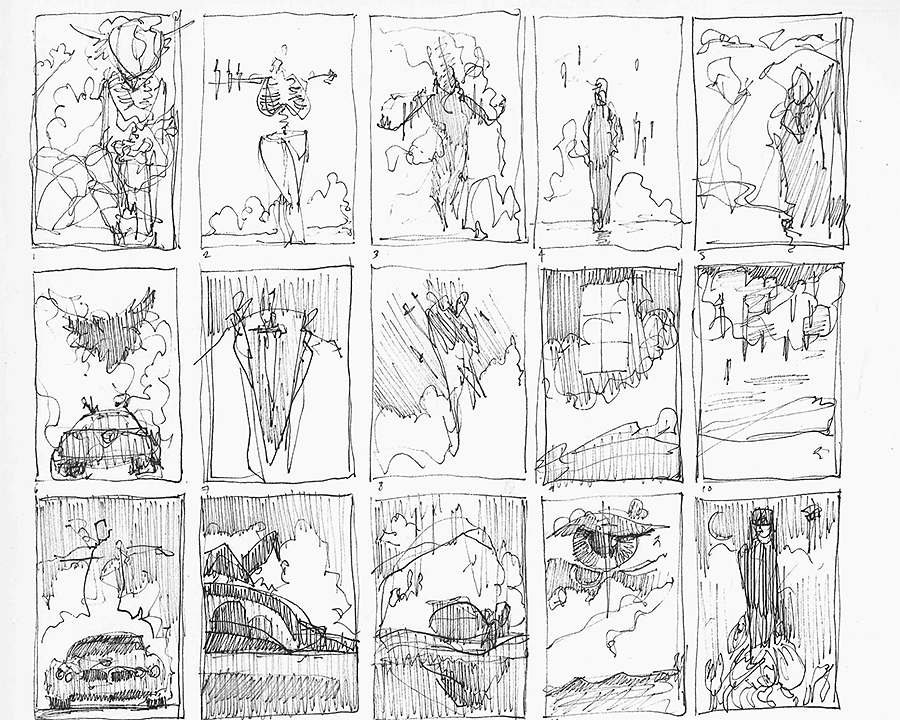

Focus on producing variations of the idea, as many as you can in the time that you have. Ideally you will end up with a sheet (or maybe even pages) of rough sketches that collectively explain your idea. They should all be slightly different from each other. It’s about quantity over quality at this stage of the development.

However, it’s easy to misunderstand ideation drawing and get caught up in how the drawing looks, especially if you are working as a visual artist or designer where the end product is tied to its aesthetic value. Try to avoid this and to focus on presenting just ideas. This is easier said than done and it does takes practice.

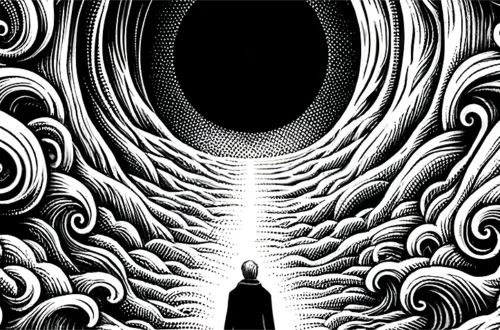

What does ideation drawing look like?

Development and ideation drawing from different fields of creative practice can naturally look very different. The ideation drawing of one artist might differ a lot from another and the difference between disciplines and applications of ideation drawing can be considerable. There is no absolute standard. Generally speaking this type of work will look rough and sketchy.

Usually, but not always, ideation drawing is monochromatic in appearance and usually carried out with a line drawing tool such as a pen or pencil. Having said this I’ve seen ideation done in many alternative formats, even watercolour and loose paint and ink. It absolutely depends on the medium being planned for and the type of end product you are trying to plan for.

When I am working with students studying painting I try to encourage them to use little boxes for each separate sketch. Commonly when doing ideation for painting they are developing ideas for a range of compositions. When you are developing an image composition it is important to consider the edge of the space as much as any other element within the arrangement.

The proximity of elements within the design to the edge of the surface you plan to paint on is equally important to their relationship with each other within the picture space. Drawing within boxes is appropriate for this type of ideation for that reason. If you were trying to design a product or an object of some sort then there would likely be no need to draw within a box. The method should be suitable for the task.

The characteristics of good ideation drawing

- the drawing should not be refined or reworked endlessly to make it look better

- each drawing should be achieved within a limited amount of time and ideally the time applied to each drawing should be more or less equal

- drawings should convey an idea or a variation on an idea

- a successful series of drawings might also show progressive development of the theme

Why is ideation drawing so difficult?

Creative thinking generally is more difficult when you are not used to doing it. Ideation can be a particularly difficult stage of the creative process because it requires your brain to innovate and alternate between possible versions of an idea that you have likely just started focussing on.

It is difficult to think of variations of ideas for a start. Often when I watch my students start to learn about ideation drawing I see them struggle with this. Your ideation thinking is like a muscle that needs exercise. It’s like going to the gym and doing your first workout, it’s difficult and your brain is trying to force you to abandon the task and do something less stressful that requires less concentration.

How to improve at ideation drawing

Let’s look here at some specific methods of helping to build your ability to ideate. Remember that it takes effort and concentration. Ideation does not come easily when you are starting out especially but here are some of the barriers and advice on how to begin to overcome them;

Get more experience in your subject area

Ideation will work better for you if you have some mental tools to draw upon. One of these is your inner library of inspiration. It is important for you to continue to look at the work of other practitioners both contemporary and historical to build an awareness of what is out there in your area (and other areas). This will help you when it comes to ideation. Details, compositional arrangements, colour schemes and other influential factors will get filed in your inner library.

When it comes to ideation, these details will help to give you inspiration to fuel your development drawings. Nothing really comes out of us as new. Usually whether consciously or unconsciously we are creating ideas from snippets of other things we have seen. Feed your ability to do this by building your inner library and study other practitioners in your area to do this.

Avoid getting stuck on one variation

We cannot usually help but get stuck on one of our variant ideas early on in the process. I’ve seen lots of people working on ideation drawing who can’t really see past the first idea. They constantly go back and adjust it when they should be working forward and creating new variant sketches.

Ideation drawing is a habit fighting exercise and it requires a will of iron not to do this. Working quickly does help, if you allow yourself only thirty seconds for each drawing and set a timer to remind you to move on then you will be less likely to invest more time in one sketch.

Fighting the obsession with one idea is a meditative task also. Being aware of your own thoughts as you work and supressing the desire to focus on that one idea develops your self-discipline. This is, needless to say, is a good thing for your productivity. In extreme cases when I have found myself struggling to move past that one sketch I have erased it from the page, I’ve found that can help me to move forward and on to other thoughts.

Use suitable drawing tools for the task of ideation drawing

As I alluded to above, there isn’t really a wrong tool for the job. It’s personal preference ultimately when it comes to which tool you use to draw your ideas with. If you are trying to draw ideation on a smaller page that requires a level of detail and you are using a blunt charcoal stick…well, I’m sure you understand the difficulties this might present.

I’ve also found personally that even a drawing tool that annoys me will destroy my concentration. A pencil that is too soft and requires constant sharpening for example. This breaks my train of thought and makes it difficult to get in to a flow of ideas.

Avoid evaluating, correcting or refining ideation in progress

One of the important aspects of ideation drawing is getting into a state of ‘unfocused focus’. You want to be able to produce volume of drawings here without getting sucked too far into any single drawing. This is harder than it sounds. You need to train yourself to do this and re-enforce the brain wiring that helps you do this successfully by repeated practice.

Attempt to skim lightly from sketch to sketch letting your subconscious mind produce the forms, patterns and compositions without being too conscious of evaluating any singe sketch. Avoid evaluation at this stage, you can do that later. Leave in mistakes, don’t redraw or refine any single sketch too much. As soon as you get hooked by one of the drawings you lose the ability to move on to the next one easily and the thought process stumbles.

Think of this task as being analogous to skating on thin ice, if you stop too long in any one spot you will fall through the surface. Keep it moving, keep the analysis and evaluation for later.

Beat the difficulty of coming up with numerous alternatives

With almost every ideation drawing session you reach a limit. The variations dry up eventually and you run out of steam. If you are only managing to produce two or three variations, or none then this can be a problem. This comes with practice of course and is easier when you are in a good frame of mind for task.

There is a technique I use when I am struggling to produce compositional variations. I imagine the scene in 3D space and think of my mind’s eye as a camera moving through and around that scene, looking at it from different angles. Every now and again I take a snapshot from this mind’s eye camera and each of those is a ideation sketch. Like a film director I might reposition the actors from time to time to make a shot look better.

This might sound like it only works for ideas that are traditionally representational but it can also work for abstracted compositions. If you break the elements apart and re-arrange them in 3D space in your mind an abstract composition can become a type of (imagined) traditional picture space. This allows me to produce many variations of an idea from all different angles.

Use the same technique to adjust the lighting in your scene. You are the director of this movie remember so it is all under your control. Occasionally I might even draw a little plan view of a scene with the elements placed like a photography studio diagram, looking down from above. Using this type of mind imaging can often help you push past the point where you can’t think of any more variations.

What to focus on when you are doing ideation drawing

So now you know what ideation is about try focusing on the ice skating technique mentioned above, think of your process as having to keep moving. It might help you to set a timer for each sketch, something around the 30 second mark. Less if that seems to get you sucked into drawing too much detail. Try to move lightly from sketch to sketch without thinking too analytically about any one of them. Remember that when you stand still too long you will fall through the ice so keep it moving and keep it light. Keep the camera of your minds-eye moving round your scene or through and around your elements.

Remember it is about variation and working roughly, sketch the larger or more important forms and elements these are likely what the idea will be built around. Details come later, good drawing comes later. This is about the arrangement of the larger shapes at this point. Later in the process when you start to refine the ideas you can start to add details and make a better quality representation.

How I learned the value of ideation

The first lesson was a real epiphany moment when I was studying design as a subject in further education college in Glasgow. The class was predominantly younger students like myself with the notion to be artists or designers of one type or another. We were all very inexperienced and naive in our process and level of commitment. We were set a task to design a label for a bottle of Sauvignon Blanc for presentation to the class the following week.

That weekend I produced a few ideas that were unspectacular but later in the day, unsatisfied with my work, I came back and decided to produce a whole page of ideas. At the class that week I turned up with a better design than I would have had I stuck to the two initial ideas and I presented my development work proudly to my tutor.

The tutor was fairly pleased and the project was marked off as completed satisfactorily. I was satisfied that I had reworked my project to produce a good half dozen variations. Most of the committed students had done the same so I counted myself smugly in the top half of the class.

The power of variations

That sense of smug self-satisfaction quickly turned to shame as the next student presented a whole sketchbook full of ideas for his label. Variation after variation, page after page. It looked like he had achieved a Herculean task over the weekend. We were all stunned by this, including the tutor. His finished label was head and shoulders above the rest in its sophisticated simplicity.

That taught me starkly the value of variation. We asked him how did you manage to do this in one weekend? He shrugged his shoulders and said “I just stayed at home and worked”. That was the second biting part of this learning experience.

Lifelong lessons learned

It dawned on me there and then that being exceptional at what you do requires commitment and a sacrifice of time and other pleasures. While the rest of the class had done just enough to complete the task, and spent most of the weekend partying, he had went above and beyond. He had dedicated the time he needed to excel. That lesson has stayed with me all of my adult life.

The other experience that taught me the value of development through variation was not so much an epiphany moment as a long drawn out slog of repeated failures. I lost count of the amount of times as a student especially that I did not take enough time to resolve the idea for a piece of artwork fully.

It was common for me to feel ‘painted into a corner’ with a composition that was just not worked out well enough or a colour scheme that went off the rails. Many times I cursed my lack of preparation until it finally sank in that working the idea out more fully at the start would lead to less dead ends. For the most part that is what I do now. But not always…

Does every project need ideation drawing?

Now it’s important to acknowledge at this stage that there is a place for the intuitive in visual art. I am not saying that every single piece of work that you do should be ultra-developed and worked out in all detail. Sometimes when I do this, it kills the immediacy for me. I lose the initial energy and impetus to let the idea out.

Occasionally the work just needs to burst forth in whatever imperfect form it takes. You need to learn to discern which opportunities are the ones in which it is the time to let this happen. Experience and the development of self-awareness will help you to decide in your own practice. This is part of the reason that being aware of your own creative process and how you work is so important. Knowledge of how you work will help you decide when it is time to use this technique for your project.

Remember to have fun.

Further Reading

You can find examples of ideation drawing across a range of applications, media and technqiues on my Pinterest Board: Ideation Drawing Examples.