How to Start and Finish Your Painting, Nine Practical Steps

Paintings often have no finite end point. Deciding when a piece of work is finished can be a difficult thing for even the most experienced artist. However, many paintings follow similar stages. There are some techniques that can help guide you through the creation process. In this article, I want to address both how to get off to the best start and also how to approach the often-elusive resolution. Let’s look at some practical painting advice from the start to the end of a piece of work.

- Start your painting with a ground

- Painting the background first

- Start with broader brush strokes

- Continue with broader brush strokes

- Work the surface holistically and use selective focusing

- Make a sector by sector to-do list

- Putting in the hours and loving the labour

- Work on more than one piece at a time

- Know when to stop

- And finally…

Consider yourself in the following situation, as I sometimes find myself. You’ve spent the whole evening tinkering with that painting you’ve been working on for the past few months. It’s still not finished. Sometimes it seems to be one step forward and two steps backwards. Areas of the image constantly emerge that need ‘fixing’ unexpectedly as you work. It seems that the painting will never be finished. Your mind fills with self-doubt. You’re sick of looking at it now and you just want the damn thing to be done. Getting near the ‘finish line’ never mind past it seems almost impossible.

We’ve all been there, whether you work abstractly or representationally. I suspect that most of the painters you admire and respect have also been there, probably more frequently than you think. So what we can we do to break this cycle of lag in our production process? I’m writing this primarily as a message to myself. A reminder of how to push through the morass that I often get caught in about two thirds of the way through a piece of work.

There are several things that I try to do when I get stuck at this stage. If you also suffer from this problem then you might benefit from reading this too. This is primarily aimed at painters but could with some adjustment apply to most media I’m sure.

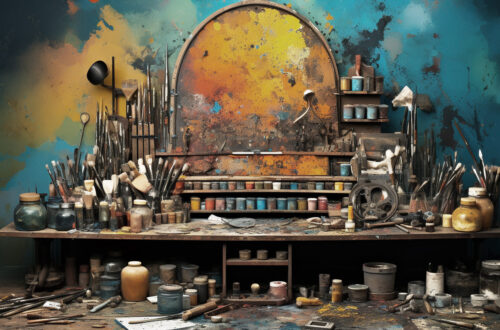

Start your painting with a ground

Good finishing starts from the outset with thorough preparation. I’ve learned from too many mistakes that making sure the surface is what you want it to be before you start is important to a satisfactory finish. That little raised area, wood chip or hair that gets stuck to the surface as you are prepping your board or canvas, get rid of it. Do it now at the first stage, I can guarantee that it will become ten times more annoying the longer you leave it there. It will almost certainly coincide with the exact area that you need perfectly flat for a focal point.

I’ve lost count of the amount of times that I’ve left a little blemish in place at the start when I’m rushing with energy to paint only to be infuriated by its presence later when removing it is going to cause damage to the surface where I’ve already created my image.

A ground is traditionally a coloured tone that is applied to your prepared surface before you start painting. It is often used as a mid-tone in the same way that you might use toned paper. It can also be used as a underlying colour layer to make the colours on top work more effectively. There are many benefits to using a coloured ground not least of which is the allowance it gives for not painting some areas. For the more experienced among you this might be a given but you’d be surprised by the amount of painters I’ve seen who have never tried using a ground colour.

When my students first try this for themselves it is often a real revelation to them. You can use any colour for a ground. You can select a colour ground that contrasts with the overall colour palette of the final image. Select a cool ground for a warmer hued image and vice versa.

Grounding the surface with colour is important for me in my technical and preparatory mental process. The ground colour I use has been developed through a lot of trial and error over the years. I eventually settled on a hue that seemed to work for the palette I most often use. It’s a greenish-mid grey ground colour which is a mix of Raw Umber, Payne’s Grey and white. I like the greenish tint below areas of painted skin especially . Using this ground helps me get the work finished quicker. It fills in the little gaps between brush strokes that you might otherwise be taking lots of time to cover. This of course makes it easier to get the painting finished as you’re not working slavishly to cover areas of the canvas or board for the sake of coverage.

There are many benefits to using a ground but if you haven’t tried it yet then give it a go. Painting on a coloured ground will change your experience. At the very least you will notice a difference in how much more quickly the work starts to look complete.

Painting the background first

If you work with paintings that use a traditional pictorial space then consider working on background first. It sounds like a simple thing but it makes sense and can save a lot of time if your painting has complex foreground or overlapping shapes. The last thing I want to be doing is having to paint around ‘foreground’ objects (hair!) to fill in background, this can be fiddly and time consuming. It is also often preferable to have the background tone established to judge your foreground tones against.

Sargent for example would paint the background over the edges of his subject before blocking in the form [source (PDF) – this is one to download and read in its entirety especially if you are a portrait painter]. Bear that in mind there is qualification for this technique. In Sargent’s case, this approach results in masterful illusions of shapes emerging or receding through uses of soft and hard edges. Generally speaking, I find that beginning with the background generally makes for a better process and resolution.

Start with broader brush strokes

One of the few useful things that I learned from my time at art school was to use bigger brushes. Especially at the start of a piece and then progress towards smaller brushes later in the process. It works well and I think that it not only makes the painting progress faster but also gives me some larger surface marks to enjoy later, if I manage to leave them intact. It’s a battle and we all have to work against the habit of adding details too early…or at all.

Continue with broader brush strokes

And now that I’ve started with a larger brush…I try to keep it going as long as possible. “Try to use a brush that’s twice as big as the one you think you should be using” someone once said to me. It’s good advice. Working with a larger brush for as long as you can stops you from getting dragged in to the too much detail too soon trap.

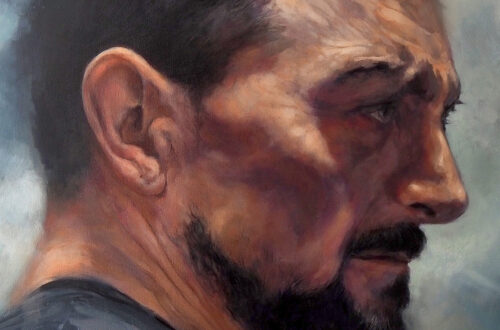

Work the surface holistically and use selective focusing

It can be beneficial to work the entire painting surface in a holistic fashion. What I mean by this is to try not to focus on one small area at a time. It is easier and quicker to get all of the basic imagery filled in roughly before moving towards any level of detail. Rather than focus on detailing one small part of the surface and over work it too early in the process, spread your effort. This allows you to apply selective focusing in the image.

Not all of the surface needs to be worked up to a fine level of detail. Some painters have and still do use a photo-realistic level of detail across the whole image and I admire this. Of course this is not required to make a successful painting. In my own work there must be some difference between an image which looks photographic and a painting. If a piece is indistinguishable from a photograph then in my opinion it’s probably better as a photograph.

For me, a successful painting should imbue the image with something beyond a photo-realistic representation. The combination of marks made by the artists hand, selective focusing, surface quality and physical presence of a painting all combine to make something that is distinctive from a photograph. No disrespect to photography as an art form intended.

Working the surface in a holistic fashion helps you bring the image into being quickly and with a more complete and together look. This can be especially useful in early stages as you struggle to set the mood and get the tonal composition working. Don’t lose sight of this in the latter stages either. You may be working on details and rendering out areas of the image but don’t lose sight of the bigger picture. Stand back frequently from the work and get some physical distance in between you and the surface. Doing this will give you a better overview.

Make a sector by sector to-do list

When I’m on the latter half of a painting I usually get to a stage where I can see that there are particular areas of the painting needing refinement. It helps to make a list of these areas and what needs done in each of them. It can help you to focus and keep on task for the bits that really need done rather than fiddling with areas that do not really need any more work. This can lead to over-working.

To achieve this I often employ a grid technique, which calls for splitting the composition into a sectors and taking notes for what specifically needs to be completed in each area. Sometimes, I might also take a photo of my painting and bring it into Photoshop. There I will make more radical changes to uncertain areas to try to resolve them. After using these techniques, I usually have a much clearer picture of what still needs to be done.

Putting in the hours and loving the labour

In the finishing stages of the painting I find that there is no alternative but to select a bit of detail get stuck in and try to enjoy working on that area. This can be the most productive way to work. There will be areas that I am avoiding because I know they will require intense concentration and real effort. Invariably when I just sit down and put in the hours in on it, this is productive and I end up loving the intensity of the concentration where hours will disappear.

When it goes well it becomes almost meditative. While perhaps daunting at first, learning this self-discipline is important. We’ll cover more of this in future articles.

Work on more than one piece at a time

It’s a simple strategy and does not always work for me. I find going back to a piece of work that’s been lying dormant for a while to be occasionally difficult. Some of my friends swear by it though. When they get bored with the struggle of one piece they find that switching to another piece of work can re-invigorate their interest again and make it easier to go back with enthusiasm when the time is right. Although it isn’t my usual approach, it is a good technique to have in your arsenal and perhaps experiment with if you are feeling stuck on one painting.

Know when to stop

Often we carry on fiddling with a piece of work when it is past time to stop. This is at best unproductive and at worst damaging to the work, it is easy to over work a painting when it’s past the point of needing anything done. This is a step that many artists experience and must learn how to manage over time. Recognize the signs of your fiddling and resist the temptation. Fiddling late in the process is fruitless; if you could can avoid it, your paintings will be better off.

And finally…

Ask yourself if you are you hiding the fact that you don’t want to finish the work because either you feel it is not up to standard or because you have the fear of what needs to be done next. I have become aware of delaying tactics sometimes in my own practice, particularly towards the end of a piece. It takes good self-awareness to realise that you are doing this and the strength to follow that up with definite action. If you sense yourself using these tactics as I sometimes do, remember to check in with yourself and honestly evaluate why you are doing so and what the best step forward is.

Completing a piece of painting can be a mental mountain to climb. If we equip ourselves carefully and do the preparatory work then your chances of success are so much higher. Good luck.